A rancher, a hiker, and two scientists walk into a bar… here’s what they have to say about Colorado’s newest residents.

A Gray Wolf looks ahead next to it's leftover prey (Photo: Greg Root)

While many Americans were perfecting the art of making sourdough during the pandemic, hundreds of Coloradans were campaigning to bring back the gray wolf. They collected 200,000 signatures, manned phone banks, and even risked their lives holding roadside signs encouraging votes in favor of Proposition 114. When it passed by a narrow margin–50.91% for and 49.09% against–in November of 2020, it was the first time in American history that a state had voted to reintroduce a species.

The gray wolf is native to the Centennial State, but by the late 19th century, the U.S. government was paying residents to kill the predator. Each dead wolf was worth $0.50, or about $11.32 in today’s money. It’s estimated that systematic poisoning alone during this time was responsible for offing up to 100,000 wolves per year. In 1945, Colorado’s last wolf was captured and killed in the San Juan Mountains in Conejos County. But around 10 years ago, wolves from Wyoming started migrating into Colorado’s North Park, 10 miles south of the Wyoming state line and 70 miles northeast of Steamboat Springs. This, mixed with successful reintroductions in neighboring states left conservationists wondering if wolves could stage a comeback in Colorado, too. If so, it would create an uninterrupted wolf habitat corridor running all the way from the Arctic to Mexico.

Three years after the passing of Proposition 114, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) is now tasked with managing the wolf reintroduction. Over the next 3-5 years, it will release 10-15 wolves, annually, on Colorado’s Western Slope near Vail, Aspen, or Glenwood Springs. While there is no target population in the current plan, once there are at least 150 wolves in the state for two successive years, or a minimum count of at least 200 wolves, they’ll be removed from Colorado’s threatened and endangered species list.

Ranchers, Young and Old, Weigh In

“There’s not a wildlife biologist in the world, if he’s being honest with himself, that would say this is a good plan for the state of Colorado,” states Greg Sykes, a Jackson County rancher. Sykes is built like a defensive lineman, but at heart he’s a sentimental softie who loves his working ranch dogs almost as much as his grandkids. That’s why he was devastated when his beloved 7-year-old Border Collie, Cisco, was killed by a wolf in March, 2023. “Cisco was the equivalent of three ranchands and knew the property better than my wife and me,” recalls a brokenhearted Sykes. Just eight months later, in November, 2023, three lambs on a nearby ranch were confirmed to have been killed by wolves, possibly the same animals that took Cisco.

Sykes, like many dissidents, thinks the state is too populated for a wolf reintroduction to be successful. Over in Kremmling, Caitlyn Taussig, a 36-year-old, fourth-generation rancher with enviable curls and a successful side hustle as a singer/songwriter agrees–but not for the same reason. While Sykes is worried about working dogs and the livelihoods of his fellow ranchers, Taussig is mostly concerned for the wolves. “Colorado is 104,000 square miles and we have almost six million people,” says Taussig who ranches with her mother. “Wyoming has half a million. It’s not fair to the wolves.”

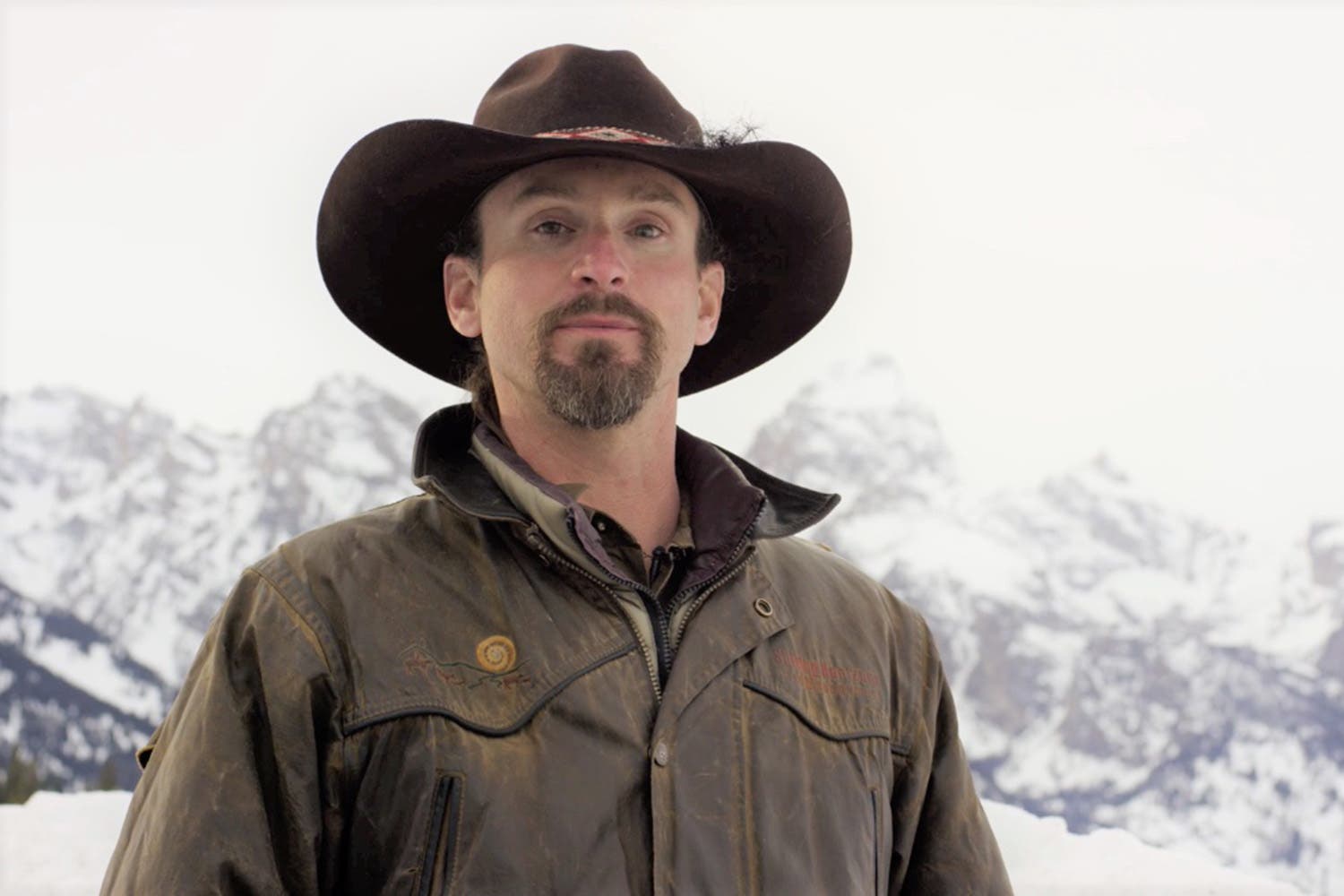

While the reintroduction will start with just 10 wolves, donated by Oregon, encounters with humans are inevitable. Even so, Matt Barnes, a scientist and conservationist seldom seen without a circle beard and a cowboy hat, thinks most conflict can be avoided. In his opinion, Colorado is in a better position to coexist with wolves thanks to lessons learned from the reintroduction of the canids to Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and Washington in the mid-1990s. “We probably know at least twice as much about wolves as a species today than we did in 1995 because they became so easy to study in Yellowstone,” says Barnes, who has worked on ranches in Colorado and Montana and now specializes in livestock carnivore coexistence. He’s looking forward to welcoming wolves back to his home state.

Great Elk Expectations

The biggest impact wolves have had on Yellowstone since their reintroduction is managing the elk population, which in turn leads to greater biodiversity within the park. For example, scavengers have more carcasses to feed on, elk are no longer overgrazing making it easier for trees to grow, and these trees provide habitat for songbirds as well as wood for beavers whose dams keep water cold for fish. According to the National Park Service and wildlife biologists, wolves have balanced Yellowstone’s ecosystem, and it all started with their impact on the elk.

With nearly 300,000 animals, Colorado has the largest elk population in the world. Some hunters fear there will be fewer animals to harvest but Joanna Lambert, Ph.D, a conservation biologist and field ecologist at the University of Colorado, believes the impact of wolves on the elk population will be “vastly less” than what some people think. “We know from wildlife agency annual reports in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho that in fact elk have increased in absolute numbers since wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone.” Lambert, a striking blonde with a perpetual tan and a passport filled with stamps after having researched animals everywhere from equatorial Africa to Costa Rica, is one of the country’s most well-known wolf advocates.

Still, Taussig, who has a B.S. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from the University of Colorado and describes herself as pro-predator (she’s learned to live with coyotes and won’t shoot them unless they come for her calves) is nervous about the possibility of an increase in elk-human conflict. “As ranchers, we deal with game damage claims from elk coming down to eat hay for our cows. I’m wondering if the wolves will push the elk down further.”

Do Hikers Have to Worry?

Sykes is losing sleep over his surviving dogs and the howling wolves his neighbors still hear. He was compensated for the loss of Cisco, but it’s not about the money. “It’s all about a dog. The wolf could have killed 100 of my cows, and I wouldn’t have gotten this much press,” he explains. “Eventually I’m going to talk to a hiker who lost their pet. I don’t think people understand the importance of a ranch dog, but a pet? They can relate to that.” Sykes has received letters and emails from strangers who say they regret voting in favor of wolves after seeing his story on the news.

Over in Boulder, Dan Lassen, an avid hiker who could pass as Chris Pratt’s older brother and the kind of intrepid explorer who travels to Georgia (the country, not the state) looks forward to the possibility of someday encountering a wolf on a trail. “I saw wolves from a car while in Wyoming. It was really, really amazing.” He says. The chances of rounding a corner and running into a wolf, however, are slim. According to Lambert, most observations in Yellowstone–where wolves don’t associate humans with negative consequences because it’s a protected area–are through 60x or 80x spotting scopes. If you ask Barnes, the risk of a wolf attacking a human is so close to zero it may as well be zero.

While Lassen and most of his hiker friends are pro-wolf, he admits they’re relatively uninformed and don’t think the decision to reintroduce wolves should have been left up to people like them via a ballot. “It should have been a decision made by wildlife experts.” Sykes, however, doesn’t even trust the pros. “One of CPW’s wolf experts sat in our living room, the day our dog was killed, and said wolves will not come into our yard,” recalls Sykes. He was grateful when another CPW employee, also present, disagreed with his colleague and acknowledged the tracks in front of the house.

Minimizing Wolf Encounters? Easier Said than Done

Fortunately for ranchers, fladry–using brightly colored flags on fencing–is legal. Studies have shown that wolves are afraid of new things, including fluttering flags which ranchers have used to deter wolves and coyotes. But fladry only works for a matter of months, as wolves eventually realize the flags are not a threat, and Taussig insists maintenance is not as simple as it seems. “We run our cattle on four different private leases in the summer. It’s rough, deep, treed country. I have no idea how you’re supposed to put up those kinds of deterrents in that kind of country. People say, ‘If ranchers would just put up fences they wouldn’t have problems,’ but they don’t know what that looks like.”

Wild burros are another nonlethal deterrent ranchers can consider. In 2022, CPW gifted six wild burros to a Jackson County rancher who lost cattle to wolves in three separate depredation events. “The idea is to make the burros become a part of the cattle herd to where they will start to protect or consider the cattle as a member of its family,” CPW Wildlife Officer Zach Weaver said in a press release. But sourcing wild burros isn’t easy, and it’s not a service CPW can provide to every rancher.

Crunching the Numbers

Taussig doesn’t think urbanites realize how much wildlife private ranches harbor and what would happen if ranches are forced to go under due to loss of livestock caused by wolves. “Ranchers are always so close to failing. We’re often cash poor but land rich, and our land is habitat for so many species. If ranchers are forced to sell, how many ranches will be subdivided and how much more habitat will be lost?”

It’s not a hypothetical situation that worries Barnes. “In a big picture statistical sense, I don’t think wolves are ever going to drive a ranch out of business,” he says. “They just don’t kill enough cattle to do that unless the ranch is on the verge of going broke anyway.” In 2022, Wildlife Services in Montana confirmed 103 livestock animals were killed by wolves. For perspective, the state is home to 2.2 million cattle and more than 200,000 sheep. In Wyoming, which has 1.25 million cattle and more than 300,000 sheep, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department attributed 97 livestock deaths to wolves in 2022.

Plus, the wolf reintroduction plan includes compensation for ranch animals killed by wolves. Between the spring of 2022 and 2023, wolves in North Park were responsible for the deaths of at least five cows, three calves and five dogs. CPW paid out nearly $13,000 for those losses. Sykes was compensated for Cisco within five days of filling out a mountain of paperwork proving the working dog’s value. But he doesn’t care about the cash. “There wouldn’t have been any amount that could have replaced him,” says a choked-up Sykes.

Recourse for Ranchers, but Not Hikers

Livestock owners don’t think getting paid market price for one lost female cow is fair. It doesn’t account for the loss of potential calves she would have had, nor does it cover health issues that arise among the surviving cattle from being harassed by wolves. But ranchers celebrated September 2023’s 10-J ruling which classifies wolves as a nonessential experimental population. It makes it legal for ranchers to kill a wolf if it’s caught in the act of killing their livestock.

Proving that, however, isn’t going to be easy. “If there’s no evidence besides a dead wolf and just a rancher with a story, then I’m not sure what happens,” admits Barnes. Best case scenario is that the game warden believes the rancher. Worst case scenario is that the rancher is charged with a federal crime. Under the Endangered Species Act, the penalty for killing a wolf in Colorado is a fine of up to $100,000, jail time, and/or loss of hunting privileges.

According to a Colorado State University study, the biggest reason residents voted in favor of a wolf reintroduction was to restore a balanced ecosystem and environment. Despite his self-professed ignorance, Lassen, the hiker from Boulder, says most of his friends feel this way. Still, Lassen admits the return of wolves could be inconvenient, or downright deadly, for dogs–which many of his friends hike with. Currently, Colorado’s wolf plan doesn’t compensate for pets killed by wolves. Nor can hikers leverage the 10-J ruling to kill one. “The reason for that is because pets basically antagonize. We want to set up a situation where you don’t have the license to let your dog run off leash, cause an incident and then shoot the wild animal involved,” explains Barnes.

Hopes for the Future

Lambert estimates Colorado’s wolf population after 3-5 years will only total 40-50 , and they’ll be dispersed on 22+ million acres. Plus, the wolves may not even stay in the state. She cites OR-7, a wolf that traveled upwards of 3,000 miles throughout Oregon and California and more recently, a wolf collared by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources that roamed 4,200-plus miles throughout three states and two Canadian provinces. “How far they go will depend on multiple factors including available habitat and prey, location of other wolves, and the individual temperament of the wolf,” says Lambert.

Sykes is praying that the relocated wolves don’t move east to Jackson County. And Taussig isn’t looking forward to having paws on her property either. “Wolf reintroduction is not a win-win for everyone, and some folks will be differentially impacted than others,” acknowledges Lambert. “The costs are unevenly distributed.” But she wants people to see the bigger picture. “These rewilding efforts are not only returning animals and plants to areas where they have been removed but also providing hope to our younger generation…hope and inspiration that they can live in a world knowing that there is wilderness remaining and wildlife that roams freely in that wilderness.”

As for Lassen, he thinks the pros will outweigh the cons. “Even if it’s inconvenient for hikers or pets, I think having a balanced ecosystem is important. Ultimately, we all need to live on this planet.”